A Glimpse Into

the untold story

SETTING THE STAGE

SNEAK PEAK

FROM THE BOOK

USS Kitty Hawk CVA-63

[Chapter One, “In the Beginning”]

"US Navy Carrier Task Group 77.7 was night steaming on a course of 335 degrees at a speed of fifteen knots on Yankee Station off the coast of North Vietnam. The guided missile cruiser USS Gridley (DLG-21) led the convoy, and a thousand yards off her starboard quarter churned the colossal attack carrier USS Kitty Hawk (CVA-63), the task group flagship.

Displacing 82,000 tons fully loaded with aircraft and armaments, and almost a quarter mile long, Kitty Hawk was one of the largest warships ever built. With an onboard air wing, she carried a complement of 4,483 officers and enlisted men. Kitty Hawk was quite literally a floating city.

Kitty Hawk’s credentials and statistics matched her massive size. Launched in May 1960, she could steam at 32 knots into a stiff headwind while launching and recovering jet attack aircraft on her huge four-acre flight deck. The ship’s onboard Carrier Air Wing Eleven had 107 aircraft, an air wing world record. That afternoon and evening, 12 October 1972, those aircraft were conducting non-stop bombing runs into North Vietnam, from just seventy-five miles off the coast of Haiphong Harbor."

A-6E Intruders

[Chapter One, “In the Beginning”]

"The Captain said it was safest to fly bombing runs at night, made possible because squadrons had Grumman A-6E Intruder twinjet all-weather attack aircraft. They could cross into North Vietnam at 500 feet altitude in pitch black weather and pouring rain. They could then drop down to 200 feet on their runs to avoid the radars of surface to air missile sites and anti-aircraft batteries. Nighttime sorties, however, meant many crew members had to work from dusk until mid-morning the next day for weeks in a row.

It was not just the unrelenting hours that contributed to the tension and stress. During the day and nighttime bombing runs, the steel bulkheads reverberated from shrieking jet engines and steam turbines driving its flight deck steam catapults and massive propulsion shafts. Sailors often took weeks, sometimes never, to acclimate to the cacophony before they got any useful sleep. And how about zero privacy around the clock, even when not on duty? Eating elbow to elbow and sleeping on a row of racks stacked three high next to another row, and another. Why don’t we bring thousands of young men of different ethnicities and backgrounds together under these conditions, most away from home and family for the first time, and see what happens? What could possibly go wrong? Plenty, as it turns out."

Subic Bay Naval Base, Philippines

[Chapter 3 “Trouble in Subic Bay”]

"On 4 September, Kitty Hawk disengaged from Yankee Station and set sail for Subic Bay in the Philippines. After completing her fifth line period since leaving San Diego in February, the sailors couldn’t wait for the much-anticipated break. Three days later, the carrier steamed into Subic Bay and tied up at the Naval Air Station dock on Cubi Point. Farther into the bay lay the Subic Bay Naval Base.

It would be an understatement to say Subic Bay was a busy port. During the Vietnam War era, over thirty Navy vessels entered the harbor each day. The Subic naval facilities at the time spread out over 262 square miles, and was the largest US Navy port in the western Pacific. It was a major supply and ship-repair facility and home away from home for much of the Seventh Fleet."

Subic Bay Naval Base and Olongapo City

Subic Bay Naval Base in the Philippines with Olongapo City in the background.

[Chapter Three “Trouble in Subic Bay”]

"Just beyond the Naval Base’s main gate and a bridge lay Olongapo City, the quintessential Navy town for sailors on liberty. During the escalation of the Seventh Fleet’s operations in 1972, however, Olongapo was overwhelmed with sailors because all the Seventh Fleet’s ships used Subic Bay’s port services. From January to October of that year, more than a million sailors were on liberty in Olongapo, with the liberty party reaching 20,000 men some nights.

On entering the town, a sailor found himself in a whole new world, appearing to some as exotic but to others as seedy. From Magsaysay Drive to Rizal Avenue and beyond lay endless bars, night clubs with live music, tattoo parlors, restaurants, and brothels. Turning left at the Rizal traffic circle led to the “jungle,” an area dedicated to attracting Black servicemen. Turning to the right sent you to the “strip,” an area where mostly white sailors hung out.

Captain Anthony Carlucci, the CO of the carrier’s Marine Detachment, believed Olongapo provided the perfect catalyst for interracial confrontations, since it was, to all appearances, a segregated town. He said the segregation fed “rumor upon rumor” that went unchecked by anyone."

San Diego Naval Air Station

San Diego was home port for several of the Seventh Fleet’s carriers, the Navy’s largest warships. The Eleventh Naval District’s facilities were sprawled over more than four square miles in and around San Diego Harbor, a natural deepwater anchorage. When in port, Kitty Hawk docked at the US Naval Air Station on North Island.

It was a city within itself. With all ships in port, its population swelled to over 30,000 military and civilian personnel. Considered one of the best US Naval stations anywhere, it had every convenience and accommodation a sailor could hope for: Commissary, Navy Exchange, enlisted clubs, movie theater, parks, and beautiful sand beaches.

San Diego Naval Station Brig

The Naval Station brig was one of the Navy’s major correctional facilities. The Kitty Hawk defendants were unjustly incarcerated before their trials, although presumed innocent. Some spent months in pretrial confinement. Those held in the maximum cellblock suffered the most, including one of my clients who attempted suicide.

[Chapter Seven “Adding Insult to Injury”]

"After the vans pulled into the brig courtyard, the chain link gate closed, and a Marine sergeant ordered the twenty-one new prisoners to exit and fall in line on the tarmac. Brig security had been alerted that there might be trouble, so a dozen Marine guards waited for them, nightsticks held at the ready. There could be no mistaking, they meant business.

By now, some of the defendants were openly venting their frustration and anger. They were escorted across the compound to one of the outlying buildings, and then taken onto the Q deck of the maximum cellblock. The sailors immediately sensed that something wasn’t right when they saw the rows of small cells encased in steel bars. As the Marines directed them toward the cells, some reacted by yelling at the guards, who in turn shouted back at them. The situation escalated and the Marines wielded their nightsticks, trying to force the prisoners into the cells."

San Diego Naval Station Law Center

The Naval Station Law Center was a quiet, nondescript one deck structure that looked over the San Diego harbor. It was the setting for the special courts-martial trials of the Kitty Hawk defendants in early 1973. The trials were front page news and drew national media attention for months.

Law Center Courtroom

Navy officials withheld crucial evidence from us Kitty Hawk defense lawyers from the outset, which resistance continued throughout the trials. They even kept secret the existence of the Navy’s major investigative report into the incident. When that report was discovered, they refused to produce it as required by military law, falsely claiming it contained classified information. The withheld evidence included sworn eyewitness statements that would have exonerated certain defendants, and which were produced only after the trials of those accused were over, including at least one defendant who was wrongly convicted.

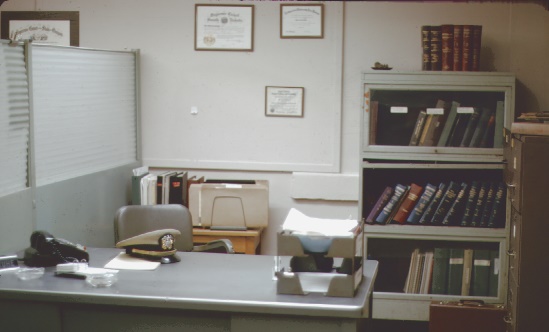

LT Truhe Law Center Office

[Chapter Eight “Kitty Hawk Lawyers”]

"Captain Newsome, the Law Center director, came by my office and handed me a list of names of twenty-one Black sailors charged in the Kitty Hawk incident. He had penciled in my name next to five of the defendants. I was later assigned to represent an additional defendant. My clients were each charged with one or more assaults, and all but one were also charged with rioting. My two youngest clients were nineteen, one having been in the Navy just six months. My oldest client was twenty-two, with over three years of Navy service.

With one exception I was aware of, every new lawyer at the Law Center began as a defense counsel. The standing joke—but not actually a joke—was that the Navy wanted all on-the-job training and mistakes to take place on the defense side of the courtroom. After several months, the now more experienced lawyer could be entrusted to represent the government and prosecute."

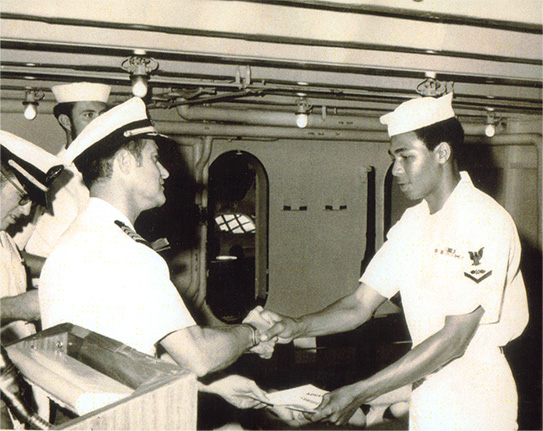

Seaman Cleveland Mallory

Seaman Cleveland Mallory was brutally assaulted by three white sailors when exiting his work station and struck with an iron pipe, fracturing three of his ribs. The onboard investigators refused to let him make a sworn statement, even though he thought he could identify his assailants.

[Chapter Sixteen “Unequal Justice”]

"The onboard investigation generated 136 sworn statements. A full three months after the incident, our defense team finally received copies of 96 of those statements, but only two of those 96 were from Black sailors. A senior first class petty officer was openly critical of the investigation. He said, “Investigators were beating a path back and forth to sick bay soliciting statements from white victims . . . [so] I asked them why they were not getting statements from blacks who were also injured and I was told they got one statement from a black.”

The investigators also took extensive oral testimony from crew members. As with the sworn statements, however, that testimony came almost exclusively from white crew members. Commander Cloud said complaints were made “that the preponderance of the witnesses . . . that had testified before Captain Haak’s investigation were all white, in excess of a hundred, with only maybe two or three, at the most, blacks being allowed or invited to testify.”

Seaman Apprentice Durward Davis

Seaman Apprentice Durward Davis was walking down a passageway alone when five white sailors saw him and started running toward him. They knocked him down and began hitting and kicking him. With so many attackers, he couldn’t defend himself. Suddenly, it was over, and the white sailors began running away. Luckily for Davis, a group of Black sailors saw what was happening and had come to his rescue. His assault was never investigated.

[Chapter Five “A Time to Remember”]

"Davis and a group of other Black sailors barricaded themselves in the forward mess compartment. Another Black sailor joined them, exclaiming that more Marines were arriving by helicopters, armed with M16 rifles, to assault them and break down their barricade.

Captain Townsend said on several occasions that evening he was approached by agitated and fearful Black sailors yelling, “They are killing our brothers!” Each time, he tried to calm them by saying, “show me,” but he said “they were truly hysterical people."

Airman Apprentice Perry Pettus

Airman Apprentice Perry Pettus took a lot of pride in his flight deck job on the Kitty Hawk, and experienced very little racial discrimination while on duty. Perhaps that was because the flight deck was the place on the ship with the highest risk of personal injury, and everyone had to look out for each other. In its best moments, he said it was “like a symphony,” with all hands working together. But then came the moment which stays with him to this day. And that was just the beginning.

[Chapter Four “A Night to Remember”]

"As we were walking across the hanger deck, a couple of Marines came up and one said, ‘You blacks, quote, you blacks, can’t walk in over twos.’ We’re thinking, yeah right, and we kept on walking. The Marine made the comment again. Puleeze, I’m going to have a Marine tell me I can’t walk with two of my friends. The next thing I know my body is up against an A-6 aircraft with a nightstick under my neck.”

Preface to the book

"The date was October 12, 1972, during the latest escalation of the Vietnam War. The place was the Gulf of Tonkin in the South China Sea. The attack carrier USS Kitty Hawk was launching bombing runs onto North Vietnamese targets. At the same time, below her flight deck, and through her labyrinth of passageways, numerous interracial confrontations erupted. It began with white Marines assaulting Black sailors and then white and Black sailors assaulting each other, sometimes armed with makeshift weapons including wrenches and broken off broom handles. When the tumult finally ended several hours later, fifty - one crew members had suffered injuries for which medical reports were issued.

By the time Kitty Hawk disengaged from Yankee Station and headed back to port in the Philippines, twenty-five Black sailors were charged with rioting and with committing assaults on white sailors. Not a single white crew member was charged at that time.

A few weeks later, my life became inextricably linked with those Black sailors. My naval officer’s uniform bore the military rank and insignia of a lieutenant in the Judge Advocate General’s Corp. I was a JAG lawyer assigned to defend six of the accused in a series of special courts-martial trials at the Naval Station Law Center in San Diego, California.

The unofficial Navy record of the Kitty Hawk incident, as well as virtually all other published accounts, would lead you to the likely conclusion that the sole perpetrators of the disturbance were Black sailors, and all white sailors aboard that night were innocent victims and bystanders.

Since this is a first person account, it necessarily includes my personal recollections. I am aided by my original case files, interview notes with clients and witnesses, and dozens of cassette tape recordings I dictated at the time. I also drew upon my personal copies of voluminous official Kitty Hawk documents including witness statements, investigative reports, and trial and hearing transcripts. Finally, and importantly, you will hear from former Kitty Hawk defendants and Kitty Hawk lawyers who shared their stories with me for this account.

During and after the trials, I assembled all the documents so someday I could bring to light the full Kitty Hawk story. That time is now, because even fifty years later, no publications or other accounts have captured the complete story, and too many have gotten it completely wrong.

Almost none have included the perspective of the Black sailors aboard the Kitty Hawk that night, let alone the viewpoint of the twenty-five accused. The New York Times did cover some of the perspective of defense counsel, often using me as a source.

The trials in early 1973 garnered national attention for months, and local television stations carried virtually nonstop reports. Print reporters set up camp outside the Navy Law Center, vying for a seat in the overflowing spectator section of the courtroom. Articles flowed from newspapers and newsmagazines throughout the country. More often than not, their headlines trumpeted “USS Kitty Hawk Race Riot!” When the trials began, a group of picketers were marching outside the gates of the Naval Station with banners proclaiming, “Free the Kitty Hawk 21!”

Politicians even joined in. A US congressional subcommittee conducted daily hearings to investigate the Kitty Hawk incident. On January 3, 1973, just before I walked into a military courtroom to defend the first of my clients, the congressional subcommittee released its report to the national press:

The subcommittee is of the position that the riot on Kitty Hawk consisted of unprovoked assaults by a very few men, most of whom were below - average mental capacity, most of whom had been aboard for less than one year, and all of whom were black. This group, as a whole, acted as "thugs" which raises doubt as to whether they should ever have been accepted into military service in the first place.

As you will see in this narrative, virtually every assertion in that statement is pure fiction.

I was honored to wear the uniform of a US Navy officer, and am proud of, and eternally grateful for those who have worn military uniforms in defense of our country. You will read about some of them here. There are others, however, whom I have less respect for, and you will read about them also.

I witnessed racial injustice up close and personal while representing the Kitty Hawk sailors. My defense of those sailors remains to this day the most challenging and emotionally charged experience of my entire legal career.

This, then, is the untold story of the Kitty Hawk incident and the trials that followed.